Fair warning: This will be something of a stream of (mostly) consciousness or subconscious—it’s hard to know sometimes.

In the UK, it is summer holiday time, schools are out, folks are off on vacation (or staying at home), and the lockdown is eased (though we know the damned virus is still circulating), and for me it is time to catch up with writing and reading. Both have been much harder to accomplish during these past few months than I thought or expected them to be.

On the writing front, the first round of edits on Seven Deaths of an Empire (Solaris, 2021) are done (2nd round incoming soon), and writing on a possible sequel approaches 100,000 words. With reading, now that I am not judging the #SPFBO for Fantasy-Faction this year, I can turn to the pile of books I’ve accumulated, long wanted to read, but never had the time—and that’s where I am going to focus here.

I set off on holiday with a factual book I’d had to find second hand and one fantasy novel I’d had on my shelf for a year or two. What I didn’t know, or realise, was how much they had in common. I’ll try in my imperfect way to make the links I saw between them.

The first book, Terrible Lizard by Deborah Cadbury, piqued my interest by being mentioned in Bill Bryson’s A Short History of Nearly Everything—which I’ve written about for Fantasy-Faction before—and also because it is about dinosaurs. Since the age of whenever it was that someone first uttered the word dinosaur to me and showed me a picture of a stegosaurus, I’ve loved the very concept of those massive beasts. I am pretty sure I am not alone in that.

Anyway, this book tells the story not of the dinosaurs, but of the scientists, amatuers, and clergymen who first put names to the giant bones and teeth they were unearthing in the UK and elsewhere. It is a factual account of those years from around 1800 to 1900, but it is also a closely woven story which references every source—incredibly well researched—and reveals the brutality of science.

These men of learning (initially paying a pittance to the woman whose skill and determination found the fossils) were playing for high stakes and some cared not a wit for who was trampled in their search for glory. There are lies, backstabbing letters and conversations, plagiarism, religion, and eventual poverty, death, and madness. It may have been a golden age for the science of geology and palaeontology—but it was built on hard work, broken fingernails, crushing defeat, and vindictive revenge.

All right, not everyone involved was quite ‘that bad’, but running through the process of discovery is a class-based hierarchy of who is right and who is wrong. Religion plays its part, on both sides—Reverends and Vicars argued about the formation and age of the earth. Noah’s flood or many floods or no floods. It is worth remembering that the clergy were still amongst the most learned men in England, and generally had the time and wealth to pursue their interests. Those without wealth struggled.

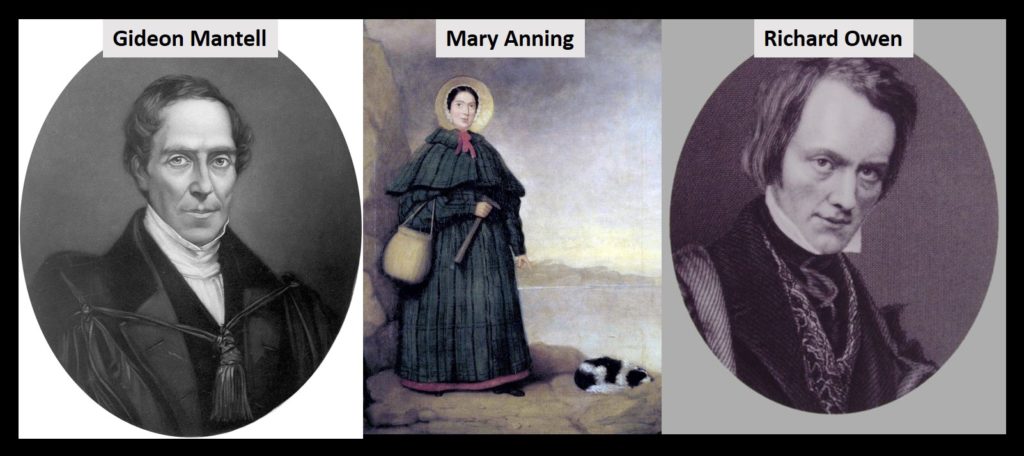

Gideon Mantell, the man who discovered (though that’s a term fraught with misunderstanding on all sides) dinosaurs was a doctor, but worked all hours, was not rich, and met with such misfortune that it is hard to believe he was not living under some hideous curse.

Richard Owen, the man who founded the Natural History Museum, wanted wealth, power, glory and fame. Yet also strove to win marriage to the woman he clearly deeply cared for, his social standing not being sufficient as a young man to make such a match.

And Mary Anning, the true fossil hunter and expert, who walked the cliffs near her home finding the bones upon which these men made their fortunes and names.

Their battle, fought by politics, letters, references, and friendships was just as viscous as one fought with swords and axes.

And then I read The Court of the Broken Knives by the incredible Anna Spark Smith. This book, of which there is deserved fulsome praise to be found here, which I don’t intend to repeat that (though I easily could). However, you’ll know this book is famed for its dark characters, its bleak recounting of power struggles, all told in beautiful, almost Shakespearean prose.

It is a book you read in short doses, a chapter or two, put to one side for a short time and absorb, think about or go out into the sunshine just for a moment to remember that the world, while cruel at times, has moments of lightness. You’re dragged back by those characters, hoping nothing more awful can happen to them or, in some cases, wishing it would. No one is an innocent—except, perhaps, that poor five year old girl.

Anyway, what struck me in reading both, back to back, was the duplicity of people who considered themselves educated, exalted above others, wealthy, and charitable. In both books there are characters and historical figures who lived in tall towers of ivory, and in both some of these towers crumble (though in Knives—they more melt than crumble, and a lot more people die).

Also, it is worth pointing out, to my mind, that in both books it is the male characters who are making most of the decisions—the fictional world echoing the factual world of 19th Century sciences. In both, the women suffer, for the most part, due to the obsessions, and desire for power and recognition. Perhaps strange how close the Empire of Dust is to Victorian England?

However, in Terrible Lizard there are moments of stupendous leaps of imagination, of realisation, perception, and intellectual brilliance. It tells me that, while I enjoy fiction which delves into our darkness, I also need moments where I realise we live in the light—and if that’s not appropriate to our times right now, I don’t know what is.

Maybe I’ll go read Guards! Guards! again, just before I dive right back into the next dark book.