In April of last year, the Twitterverse erupted with charges of cultural appropriation in Jay Kristoff’s debut, Stormdancer. I took the accusations with a grain of salt, since the term is bandied about with knee-jerk abandon, and decided that one day, I’d dig Stormdancer off the slopes of Mount TBR to find out for myself.

For the two of you who follow my articles (my daughters, who wouldn’t read them if I didn’t withhold dinner), you know I don’t really read as much as listen to novels; so that one day probably would have become never had I not been able to snag the audiobook for $2.50.

Although I lived in the Japanese countryside for a year, married a native Japanese, read extensively about Warring States and End-of-Tokugawa eras, and watched hundreds of period and pop dramas, I am no expert on Japanese culture. Still, I know enough that two chapters into Stormdancer, I was cringing.

The premise of the story is in a world powered and poisoned by a lotus weed, the ruling Shogun has heard from his ministers about the reappearance of a mysterious griffin. He tasks a hunting party, led by the father of the main character, Yukiko, to capture it.

As a concept, it’s cool. Lotus is a metaphor for the modern fossil fuel economy, the Shogun a stand-in for the oligarchs who rule our world. However, Kristoff is already mangling the concept of Shogun (a military title) by including ministers (an imperial court position). While the Western powers trying to open Japan to trade made the same mistake back in the 1850s, I would expect better research from a novel written in the Information Age.

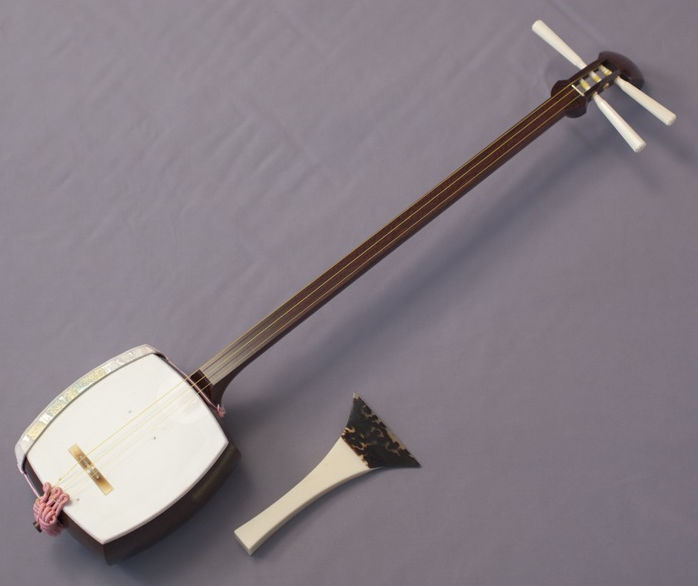

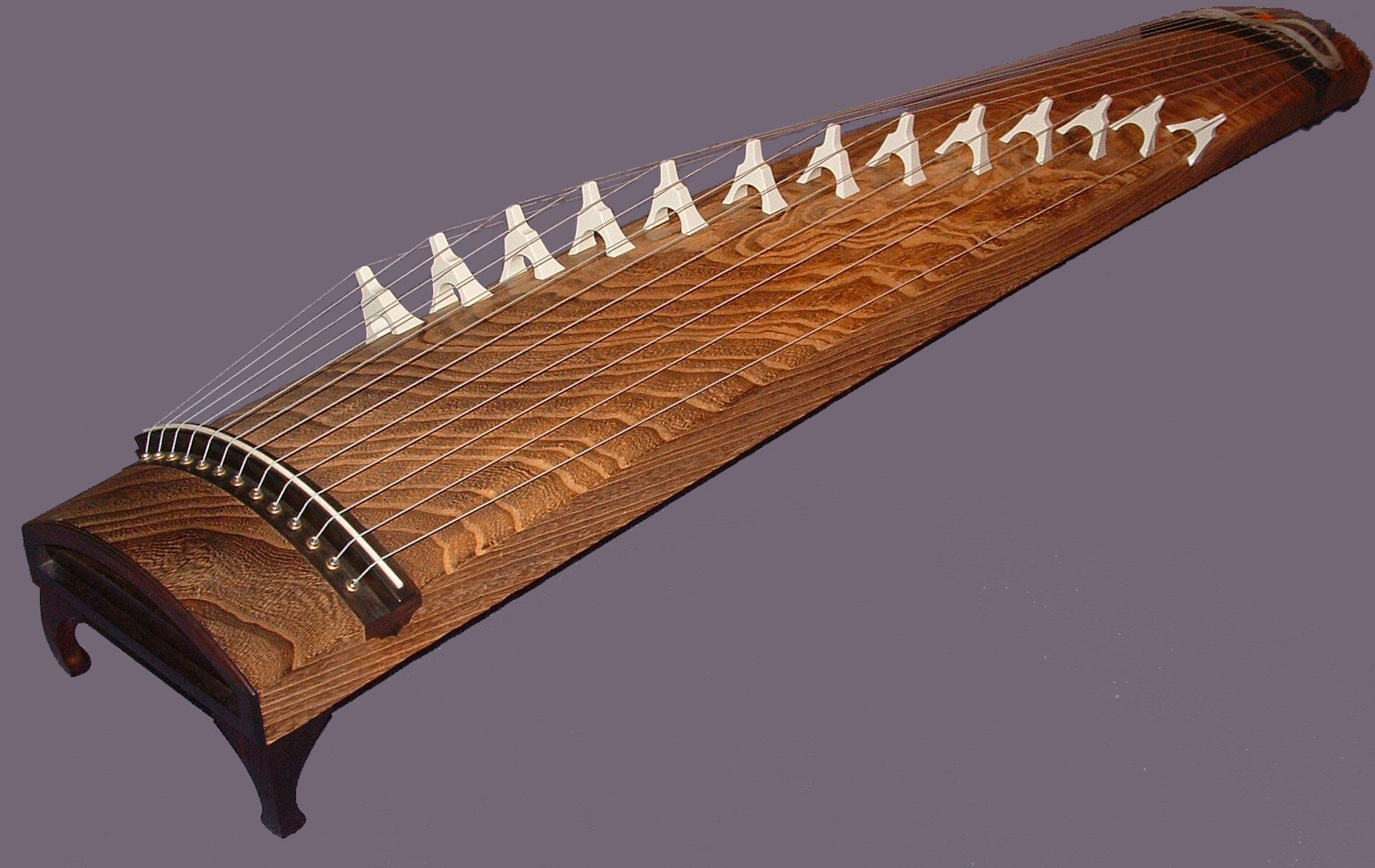

Even worse, the griffin is called an arashitora, a literal mashup of storm and tiger in Japanese kanji. When I asked native Japanese speakers what they thought it was, I got puzzled expressions. One pointed out the two kanji can be used as a nickname, but pronounced either ranko or tora. In another linguistic blunder, he mentions court ladies playing the shamisen. In reality, the shamisen is a three-stringed instrument similar to a guitar; but the words he uses to describe the instrument suggest he meant a koto, a Japanese zither.

It goes from worse to awful with the Japanese-coded characters. Any time they interact with each other, the dialog is stilted with Orientalisms. Every time they regularly end a sentence with hai instead of ne, I got pulled from the story. Really, I felt it was an unnecessary element to reinforce the exoticism for the reader.

More egregious is when they address each other as sama instead of using it as a suffix to a name. The author must have known it was a suffix, since characters do address each other with the endearing suffix –chan. It’s grammatically correct, but in socially incorrect settings. They salute each other like Chinese martial artists, with a fist in the palm. In further culture mangling, they use the Mandarin aiya for an exclamation.

When he said his research consisted of “watching anime and eating Pokky,” it might have been tongue-in-cheek, but might as well have been the case. One of the few things he does get right is Japanese mythology from the original Kojiki, though the populace in his story invoke divine beings with a historically inaccurate regularity, stripped from their Shinto origins.

I would have given up on the book, but once Yukiko is on her own, tracking down the griffin, most of the Orientalisms melt away. She, as well as other characters don’t feel like a walking stereotype like say, the protagonist of Memoirs of a Geisha (whose author was sued by the Geisha he based the story on) or caricatures that have historically appeared in popular Western media. The vivid prose makes it easy to become engrossed in the setting, to absorb other aspects of the intricate worldbuilding. The character arcs are well-developed, the tension high, and emotion impactful.

By the time she meets up with people again, I felt invested in the story enough that I not only finished but continued with book two (it was also on sale at Audible!).

Which brings us back to the accusation of cultural appropriation. Being ethnically Japanese would not make an author’s work culturally or historically accurate. On the flip side, plenty of Caucasian authors have written respectful Japanese-inspired fantasies, such as Lian Hearn’s Tales of the Otori, Raymond Feist/Janny Wurts’ Daughter of the Empire, and Virginia McClain’s Blade’s Edge. Had the author done more in-depth research and recruited sensitivity readers to fix the glaring issues, Stormdancer would easily be an 8-8.5-star story.

Had he intentionally mashed up cultures, such as in Rob Hayes fusion of Japanese Chanbara/Yokai and Chinese Wuxia in Never Die, or Andrea Stewart’s The Bone Shard Daughter, I would rate it 9-9.5 stars.

And had he created a completely unique culture like N. K. Jemisin’s Fifth Season, I believe Stormdancer would have been a mind-blowing 10-star story.

As is, I see Stormdancer the same way as Solo: A Star Wars Story. If I pretend it’s not about Han Solo, I can enjoy the storytelling. If I pretend Stormdancer isn’t meant to be based on Japan, it’s wonderful. I therefore rate it as a lost opportunity at 6 stars.

Note: If you want to read a more authentic Asian steampunk story, check out Jeannie Lin’s Gunpowder Alchemy and Clockwork Samurai, a retelling of the Opium Wars—with skyships. I also highly recommend the other books mentioned above.