Growing up, we’re taught to always be kind and tell the truth, but as adults, are any of us truly virtuous? We walk past the panhandler with a muttered “sorry,” or we pretend we don’t see them at all. We tell our boss we’re late because traffic was terrible or the cat was sick, when we really just overslept. We forget to return the borrowed book. We bail on the promised night out with the bestie. We rationalize these actions, and often, they’re justified, because, frankly, honesty is not always the best policy.

Growing up, we’re taught to always be kind and tell the truth, but as adults, are any of us truly virtuous? We walk past the panhandler with a muttered “sorry,” or we pretend we don’t see them at all. We tell our boss we’re late because traffic was terrible or the cat was sick, when we really just overslept. We forget to return the borrowed book. We bail on the promised night out with the bestie. We rationalize these actions, and often, they’re justified, because, frankly, honesty is not always the best policy.

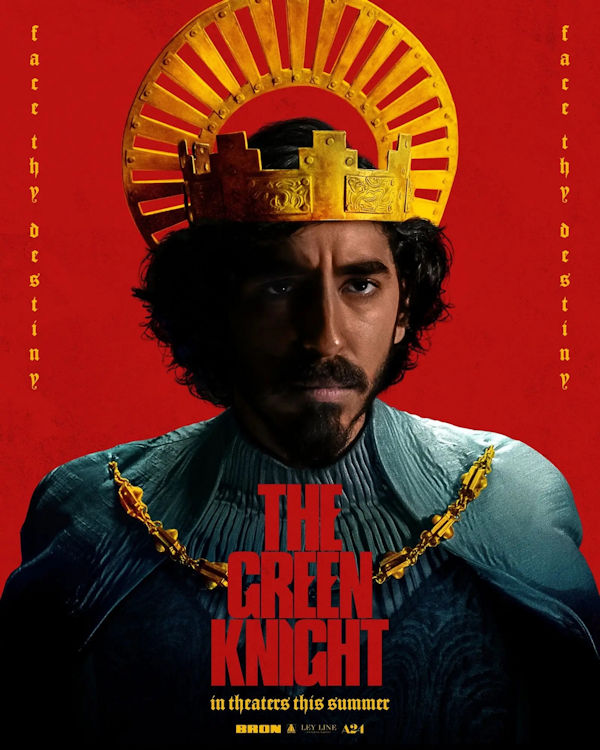

The Green Knight, recently in theaters and still on several streaming platforms, is a beautiful, contemplative, and thought-provoking film that explores the meaning and cost of honor. It’s not the Ned Stark, stick to your principles and keep your word even if it means throwing the kingdom into civil war kind of honor. Rather, this story is about an everyman—one who is equally flawed and sympathetic—and how he reacts to opportunity and adversity.

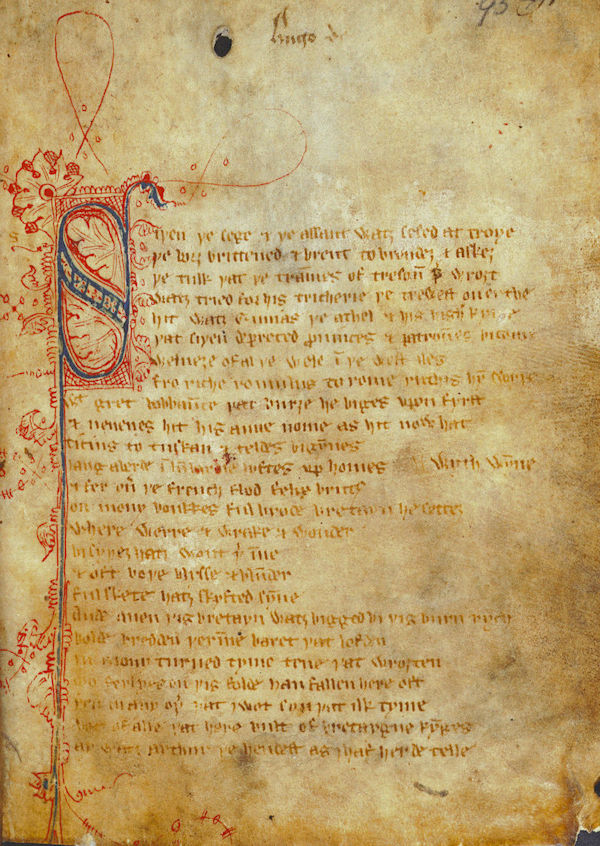

In the traditional chivalric tale “Gawain and the Green Knight,” Gawain is the son of King Arthur’s sister Morgause and King Lot. On Christmas day, a strange knight, wearing green armor and riding a green horse, turns up at Camelot and challenges the knights of the Round Table to a game in which he will stand by and let one of them strike him with an ax, so long as the challenger allows the Green Knight to strike him back, blow for blow, one year later. At first, none of the knights take the challenge, so Arthur steps forward. Not willing to let his uncle—and king—take any risks, Gawain volunteers for the game and whacks off the Green Knight’s head. Unperturbed, the Green Knight stands up, retrieves his head, and tells Gawain where to meet him in a year’s time before taking his leave.

In the traditional chivalric tale “Gawain and the Green Knight,” Gawain is the son of King Arthur’s sister Morgause and King Lot. On Christmas day, a strange knight, wearing green armor and riding a green horse, turns up at Camelot and challenges the knights of the Round Table to a game in which he will stand by and let one of them strike him with an ax, so long as the challenger allows the Green Knight to strike him back, blow for blow, one year later. At first, none of the knights take the challenge, so Arthur steps forward. Not willing to let his uncle—and king—take any risks, Gawain volunteers for the game and whacks off the Green Knight’s head. Unperturbed, the Green Knight stands up, retrieves his head, and tells Gawain where to meet him in a year’s time before taking his leave.

Gawain, being a true and virtuous man, heads out to keep the appointment a year later. Along the way he meets with a sketchy lord and lady who try to tempt and trick him into betraying his honor—or at least cheating a little. This crafty pair run a grift where the lady keeps trying to seduce Gawain. Unable to convince him to sleep with her, she gives him a magic belt that will protect him from harm. Gawain takes the belt then goes to the meeting place and submits to his impending beheading. The Green Knight reveals he’s really the tricksy lord (and husband of the belt-giver), and the whole affair was a prank engineered by Morgan le Fay as a test of Gawain’s chivalry. Magic belt notwithstanding, he declares Gawain has passed the test, and everyone has a good laugh and goes home, heads still affixed to bodies.

The Green Knight is a fairly straightforward retelling of the original Arthurian legend, a key difference being that Gawain (Dev Patel) is a mildly ignoble squire rather than a virtuous knight. His spends his time, drinking, whoring, and brawling, like an Arthurian Prince Hal. But he is also nephew to the king (Sean Harris), and on Christmas day joins the revels round a certain circular table. While he’s there, his mother (Sarita Choudhury) and sisters summon the Green Knight (Ralph Ineson), and so the game begins.

One of the intriguing aspects of this film is how opaque it is. It’s about choices and consequences, but it’s also about the murky, muddy motivations of love and ambition. My husband and I had a lively argument about whether Gawain’s mother was evil. I didn’t think so—she clearly loves Gawain and, as I saw it, had simply engineered an opportunity for her ne’er-do-well son. Gawain’s motivations for beheading the Green Knight (rather than delivering a minor wound) is unclear, and I wish there’d been more deliberation on this point, since the GK names “a scratch” as an option. However, Gawain is the sort of person who does what’s expected of him, if only so he can get it over with and get back to carousing. With the king and all the knights of the Round Table staring at him, the decision to end the game with a single quick stroke doesn’t seem all that rash. After all, who could have guessed that an antler-bearing green man—basically a walking tree—could survive such a pruning?

When Gawain embarks on his quest a year later, his prostitute girlfriend (Alicia Vikander) tells him not to go. She wants her everyman to stay alive, although at the same time, she’s keen to rise from the brothel to the throne. He leaves not because he wants to go—or feels he must go because it’s a matter of honor—but because it’s easier to go along to get along with his mother and uncle, whose expectations prod him out of Camelot. Plus, his mom has spent a year weaving a belt of protection, so no matter what happens, she assures him, he’ll come to no harm.

Magic belt or no, Gawain learns ambivalence and passivity can be lethal at the first roadblock in his journey. From then on, every decision he makes bears the weight of life and death, and the journey is filled with lessons on the cost of virtue and the price of lies.

Saint Winifred, a young woman whose would-be rapist murders her by—you guessed it—chopping off her head, appears in the film but not in many versions of the original tale. David Lowery (the director) and I must have read a similar rendering, however, because I remember one where Gawain rescues Winifred from captivity in the Green Knight’s castle. Gawain’s film encounter with this distressed damsel (Erin Kellyman) doesn’t play out so neatly, but it does afford him an important opportunity to do something good (for once) and also connects him with an Arthurian sort of kitsune.

The twisty, tricksy nature of his world comes into focus during the next episode, when he meets the grifter lord and lady (Joel Edgerton and Alicia Vikander) from the original tale. In the film, the couple are philosophical sorcerers who use Gawain’s soul as an alchemical substrate. Their home, with its anachronistic furnishings, is a place outside of time where Gawain’s motivations are scrutinized and turned upside down and inside out. They expose—and judge—his lack of agency and push him to continue his quest even as they try to keep him from it. The episode is a mirror of the whole film, which is a contemplation of opposites: life and death, growth and decay, action and inaction, truth and lies.

If you like your fantasy movies fast-paced and bloody, this isn’t going to be your film. It’s as deliberate, contemplative, and beautiful as Bladerunner 2049. It’s also a lot less straightforward, both narratively and emotionally, than that film. Gawain starts out as a lovable rogue, but he loses bits of his humanity on his journey, and what he does to reclaim his soul could cost him his life. It’s a movie I found equally fascinating and confusing, and which bears repeat watching. It’s also filled my thoughts since I saw it—several weeks ago, as of this writing. I expect it’s a film that will stay with me a long time hence.