When people think fantasy, they think elves and dwarves (maybe orcs and goblins too). And they think of them in that order. Elves are beautiful, magical, and melancholy (or eerily joyous). They have been endlessly reinvented—Blood Elves, Poison Elves, Night Elves, Iron Elves, cat-like fey sociopathic elves, soul-eating sea-elves, Zen mountain elves, wolf elves, plant elves, cereal elves, and more.

The sturdy, stolid dwarves have drifted far less from Tolkien’s original template. Many people enjoy the ‘classic’ dwarf aesthetic: grumpy, hard-drinking, good-hearted miners, crafters, and warriors with broad accents and long beards. People have made songs about them and written whole series of books about them. The concept of dwarves seems to resist change, much as the characters themselves do.

But since they bear the very concept of epic fantasy on their broad shoulders, let’s have a look at the noble dwarves and see if we can breathe some fresh life into them.

The Problem with Fantasy Dwarves

A couple of notes before we get into the meat of this article.

As modern readers and writers, we should take care to examine the source of the clichés and concepts our favourite genres are built upon. The very idea of different fantastical ‘races’ with different attributes and predilections has been linked to dangerous and corrosive ideas about human peoples, ethnicities, and societies—racism, imperialism, exceptionalism, orientalism, to name a few. As the debate around race and racism has evolved in recent years, there has been a movement away from using the term ‘race’ in RPG circles, due to its connotations. (I imagine that fantasy fiction has seen similar discussions.) D&D now uses the term ‘ancestries’, Warhammer Soulbound ‘species’. I’ve used the term race, without ill will but also without thought, in previous articles. These days I prefer the terms species or people. Time may prove me wrong once again.

Changing a word does not fix the underlying issues, however. And we should be particularly careful with Tolkien’s creations because academics have argued many of them are deeply racially charged. Focusing particularly on dwarves, John D. Rateliff, for example, said Tolkien drew upon the Medieval depiction of Jewish people as inspiration for his dwarves—particularly their association with craftsmanship and love of gold. (Which came as quite a shock to this lifelong fantasy reader.) And that tales from the Hebrew Bible furnished Tolkien with stories of a warrior people with mighty kings who eventually became corrupted by greed.

Changing a word does not fix the underlying issues, however. And we should be particularly careful with Tolkien’s creations because academics have argued many of them are deeply racially charged. Focusing particularly on dwarves, John D. Rateliff, for example, said Tolkien drew upon the Medieval depiction of Jewish people as inspiration for his dwarves—particularly their association with craftsmanship and love of gold. (Which came as quite a shock to this lifelong fantasy reader.) And that tales from the Hebrew Bible furnished Tolkien with stories of a warrior people with mighty kings who eventually became corrupted by greed.

I don’t know if Tolkien himself acknowledged or consciously intended those connections. But he certainly based his dwarvish language on Semitic languages and drew parallels between his dwarves and actual Jewish people:

“I do think of the Dwarves like Jews: at once native and alien in their habitations, speaking the languages of the country, but with an accent due to their own private tongue….”

Most of those characteristics have been worn away as dwarves were reused in new fantasy tales. The axes, gruff exterior and curious accents may remain, but the idea of the dwarves as a people without a homeland, who speak their own private language, has not survived much beyond the original stories.

I should be clear, by the standards of his time, Tolkien was not consciously anti-Semitic. He condemned the twisting of Norse mythology and European folklore by people such as Wagner, who used it to justify hatred towards groups such as Jewish people and to build a toxic fantasy of a superior Germanic race. When questioned by a German publisher as to whether he had any Jewish ancestors, Tolkien lamented his lack of connection to that “noble race”.

But Tolkien was a British man of the early 20th Century, mired in ideas of race that have not stood the test of time. Enjoying his works does not mean we endorse, or even recognise, those ideas, but we should approach his creations with our eyes open.

Dwarves in Modern Fantasy

Now. What have the writers who came after Tolkien done to make the dwarves their own? Rather than reinventing dwarves from the ground up, many writers chose to explore one or more aspects of dwarvishness and expand upon them, or shift them into different contexts.

Dwarves are hard workers who love their traditions. In one book in the Death Gate Cycle, (written by Margaret Weis and Tracy Hickman of Dragonlance fame), a society of dwarves worship the gigantic machine that aligns floating continents and is their realm’s only source of water.

Dwarves are hard workers who love their traditions. In one book in the Death Gate Cycle, (written by Margaret Weis and Tracy Hickman of Dragonlance fame), a society of dwarves worship the gigantic machine that aligns floating continents and is their realm’s only source of water.

These dwarves, or Gegs, form an underclass of workers who are ruthlessly exploited by a tyrannical society of elves, leaving them ripe for a Socialist revolution. It’s an unfair arrangement, but it still makes thematic sense. Dwarves are tough, hard-working and no-nonsense, they would naturally excel at the dangerous, backbreaking labour required of an industrial working class. They don’t question their enslavement because they’re so used to following the ways of their ancestors. Elves are beautiful, charming and have an inherent air of superiority, of course they would excel at manipulating others and of course they make excellent stand-ins for aristocrats or successful capitalists. Even their respective accents have class connotations.

In fantasy fiction as a whole, skill with machines is more often a source of power for dwarves than an invitation for other species to exploit them. Dwarves excel at steampunk—the goggles fit into their aesthetic very nicely, their love of crafting switches seamlessly from making mysterious magical artefacts to the manufacture of clanking, smoking behemoths of iron and brass.

The Kharadron Overlords of Games Workshop’s Age of Sigmar setting live in flying mechanical cities, fly around on steam-powered balloon jetpacks, and fight with rivet guns and exploding drills. Though less flashy, the dwarves of both Warcraft and the original Warhammer world have a similar interest in machines like airships and tanks, matched only by the chaotic goblins and gnomes.

The Kharadron Overlords of Games Workshop’s Age of Sigmar setting live in flying mechanical cities, fly around on steam-powered balloon jetpacks, and fight with rivet guns and exploding drills. Though less flashy, the dwarves of both Warcraft and the original Warhammer world have a similar interest in machines like airships and tanks, matched only by the chaotic goblins and gnomes.

The dwarves, or Mostali, of Runequest are something akin to machines themselves—automatons of either stone or clay. They belong to castes associated with different minerals and work tirelessly to repair the World Machine.

Sometimes writers explore a theme as a way of lampooning it.

It’s a common joke that dwarven women also have beards. The great Sir Terry Pratchett followed that thread further than most, suggesting that sexual dimorphism was so slight (or at least, hidden) in dwarves that an individual dwarf’s gender was rarely known and intensely private. Dwarven courtship on the Discworld begins with a series of subtle questions intended to determine whether the object of affection is of a compatible gender. Truly traditional dwarves avoid going above ground as much as possible and dress in conical leather robes to shield their faces and bodies from sight.

One plotline that carries on through multiple Discworld novels is the growing visibility of dwarves who are ‘out’ as female, and the backlash against them from traditionalists. In this way dwarves—hidebound, conservative, seemingly belonging to a monoculture—can be a tool that lets us examine our own societies: the things we take for granted, our beliefs about gender, personal freedom, and decency. It’s funny to imagine dwarves being scandalised by another dwarf daring to shave, and the comparison can help us realise how silly it is to be offended by a person who is assigned one gender at birth then transitions into their true gender identity later in life.

One plotline that carries on through multiple Discworld novels is the growing visibility of dwarves who are ‘out’ as female, and the backlash against them from traditionalists. In this way dwarves—hidebound, conservative, seemingly belonging to a monoculture—can be a tool that lets us examine our own societies: the things we take for granted, our beliefs about gender, personal freedom, and decency. It’s funny to imagine dwarves being scandalised by another dwarf daring to shave, and the comparison can help us realise how silly it is to be offended by a person who is assigned one gender at birth then transitions into their true gender identity later in life.

Other writers have turned dwarven traits on their head.

The Duergar, from D&D, are basically just evil dwarves (because you have to have an evil version of everything in D&D, but that’s a discussion for a whole different article). All the negative traits associated with dwarves are emphasised in duergar—greed, insularity, stubbornness, vengefulness, suspicion, lack of humour. And they have few of the positive qualities—they’re not honourable or loyal, though they are brave.

A more pleasant take on “flipped dwarves” is presented in A Scottish Podcast, which is mainly a horror story laced with dark humour but strays into epic fantasy in its second season.

Though still subterranean and reclusive, these dwarves are a mysterious culture of wizards. Of course, if you’re cutting out or remixing dwarven traits, you can always add in a few more of your own.

In the post-apocalyptic D&D setting Dark Sun dwarves are still tough, hardy and strong, but are also hairless. These dwarves are extremely single-minded and hardworking. In fact, if a dwarf dies with their current ‘focus’ incomplete, they will be doomed to haunt the deserts as a banshee, endlessly bewailing their unfinished business.

In the post-apocalyptic D&D setting Dark Sun dwarves are still tough, hardy and strong, but are also hairless. These dwarves are extremely single-minded and hardworking. In fact, if a dwarf dies with their current ‘focus’ incomplete, they will be doomed to haunt the deserts as a banshee, endlessly bewailing their unfinished business.

If you strip out the Nordic culture of dwarves completely, you can then slot in an entirely different culture in its place.

(I remembered this next series as a completely different take on dwarves to the one presented in the Death Gate Cycle, so I was surprised to discover they were both written Margaret Weis and Tracy Hickman. Once again, it was the gamers who sought to put a new spin on dwarves.)

In the Sovereign Stone series Weis and Hickman reimagined dwarves as steppe nomads who considered walking on the ground to be weak and shameful. Those who could not ride were abandoned by their tribes, left to scrape out a living in the three cities of The Unhorsed. A key part of the series is the idea of Dominion Lords: knights empowered by magical armour. This armour is too heavy for a horse to bear, and no dwarf would willingly give up their mount, even in return for power equivalent to a fantasy Power Ranger. This means dwarven Dominion Lords are drawn from the most shunned members of their society.

Jumping back to Warhammer. The original Warhammer World had its own take on evil dwarves: the Chaos Dwarfs. These guys had short tusks, long eccentric hair, and a penchant for magic and blood sacrifice. They kept vast armies of slaves who laboured in their mines and factories, or died screaming on their burning altars. They crafted terrible daemonic war machines, and eyed the lands of ‘evil’ and ‘good’ cultures with equal rapacity.

(I will note that, in an echo of Tolkien’s worldbuilding, the good Warhammer Dwarfs live in the West and the bad Warhammer Dwarfs live in the East.)

Of course, if you’re not writing an RPG or wargame then stats don’t matter, so you wouldn’t lose much by just having your steppe nomads or blood-happy slave-mongers be human (or lizard-people, or raptors, or androids).

And then, there’s Jay Lake.

And then, there’s Jay Lake.

Lake went in a completely different direction with his City Imperishable duology abandoning the idea of fantasy dwarves as a separate species to humans at all. (This immediately puts us in an uncomfortable position because fantasy dwarves are just that—a fantasy, a product of imagination. But humans with dwarfism are very much real and deserve to be treated with respect in fiction as well as in the real world.)

In the series, dwarves are a specific social class of humans created through body modification, a bit like eunuchs in Imperial China. Dwarven families maintain their short stature by horrific means—intentionally keeping their children shut in boxes to forcibly stunt their growth. This practice grants dwarves a certain social status (it may also serve a magical purpose), even as it traumatises every single one of them. Possibly worse, a few dwarves are created by taking an adult human who has achieved full growth and cutting down their muscles and bones. (Surely no one would survive that process, but this is fantasy.) Why Lake thought this was a good idea, I don’t know. But it’s certainly memorable.

If feeling charitable, one could argue the privations suffered by Lake’s dwarves may reflect some of those suffered by real world Little People, some of whom have the option of enduring incredibly painful procedures, which may increase their height somewhat. It might also reflect real world practices such as foot-binding. This is perhaps a topic another writer could explore sensitively, but I wouldn’t make the attempt myself without doing extensive research and getting advice from the real people it touches upon.

(Perhaps Lake did just that, I couldn’t say. He uses dwarves as viewpoint characters, but I’m not qualified to say whether his portrayal is sensitive or positive, particularly as his writing style tends toward the transgressive.)

Where do we go from here?

That’s what’s been done. Where might we take fantasy dwarves next? Do we emphasise some traits, flip them or pursue them to a seemingly logical conclusion? Cut some traits out? Throw in new ideas? Start from scratch?

Let’s try a mixture of approaches—here are eight ideas for different takes on dwarves.

1. Necromancer Dwarves

They live underground where the bodies go. They have few natural resources and are beset by subterranean monsters. They live in close proximity to the Underworld and its gods. Of course, they draw upon the powers of death and use vast armies of skeletons to build their gloomy temple cities. (You could even have vampire dwarves; living underground is the perfect way to avoid the sun, and their tough, bulky ribcages would resist all but the most determined stakings.)

They live underground where the bodies go. They have few natural resources and are beset by subterranean monsters. They live in close proximity to the Underworld and its gods. Of course, they draw upon the powers of death and use vast armies of skeletons to build their gloomy temple cities. (You could even have vampire dwarves; living underground is the perfect way to avoid the sun, and their tough, bulky ribcages would resist all but the most determined stakings.)

2. Woodland Dwarves

The dwarves of Snow White may be miners, but they live in an idyllic forest setting and seem in harmony with nature. A writer could draw upon Medieval European myths of hairy wild-men, which, as far as I can tell, were quite distinct from modern ideas about apes, sasquatches, and the like. These strange beings often had green fur, and wielded weapons and tools of wood. The Slavic Leshi (old man of the woods) would be another good source of inspiration. Why should we always personify nature as gracile, magical and beautiful? Let it be gruff, tough and mighty! These dwarves would be masters of stealth, climbing, trapping and hunting.

I would be careful of falling too far into ideas of cavemen or primitive savages though—people who live in the woods aren’t any less intelligent than people who live in towns, they have just had a very different education.

(It is worth noting that talk of a new Disney version of Snow White, sparked controversy in Hollywood, with LP (Little People) actors on both sides either condemning or supporting the portrayal of dwarves in the original Disney film.)

3. Imperialist Dwarves

Dwarves are hardy, industrious, often hierarchical, and more likely than most fantasy species to embrace advanced technology. With relatively easy access to metal ores, oil, and coal in their subterranean kingdoms, dwarves are the obvious choice to begin a fantasy world’s industrial revolution.

With guns, steam-powered war machines, and tough soldiers, the dwarves could conquer huge swathes of territory if they wished to (much as the Chaos Dwarfs threaten to). Instead of numberless hordes of orcs menacing the human kingdoms, it could be a well-disciplined army of dwarven musketeers. Who needs a dark lord when we could have a merchant cartel intent on plundering human lands for their riches? These imperialist dwarves could still have that Viking style culture (Vikings got all over the place so this could be a logical development of dwarven culture).

Alternatively, since dwarves are often portrayed as having one kind of British accent or another, why not make them British? There aren’t, to my knowledge, many fantasy stories based upon the British Raj regime in India, or Britain’s wars of conquest in Africa. And it never hurts to have another story that reminds us why imperialism is bad.

4. Downtrodden Dwarves

Humans are very good at imperialist oppression too, as any historian will tell you. If humans conquered a dwarven city the result could be very grimdark and nasty.

We’ve certainly seen the oppression of non-humans as a metaphor for racism in many fantasy stories, The Witcher and Carnival Row for example. Or the world of Dragon Age. However, Jeff VanderMeer’s grey caps would be a good source of inspiration too—though they’re humans of a different ethnicity to their colonisers, rather than a separate species, they have a very different culture to the newer citizens of Ambergris and are plotting to retake their ancestral home with biological (fungal) warfare.

An urban war between humans and dwarves could be exceptionally nasty. We can assume dwarves build many of their structures underground and so would barricade these homes against human invaders. Humans, endlessly and ruthlessly inventive, might pour poison into these boltholes. Alchemists could create smoke that was heavier than air and pour that into dwarven buildings to drive them up to the surface. The death toll would be grim, and the survivors would be devastated.

An urban war between humans and dwarves could be exceptionally nasty. We can assume dwarves build many of their structures underground and so would barricade these homes against human invaders. Humans, endlessly and ruthlessly inventive, might pour poison into these boltholes. Alchemists could create smoke that was heavier than air and pour that into dwarven buildings to drive them up to the surface. The death toll would be grim, and the survivors would be devastated.

Imagine this city a few generations later. Dwarves are an oppressed underclass, forced to make incredible weapons, tools, and jewellery for their human masters. But the dwarves haven’t forgotten the taste of freedom, or the atrocities committed against their ancestors. Natural diggers, with knowledge of the under-city that human’s largely disdain, they have begun tunnelling beneath human structures, collapsing them and killing those inside. The human overlords have cracked down, arresting and publicly hanging all suspected ‘underminers’. This has driven more and more dwarves into the arms of the rebels.

5. Seasonal Dwarves

Why live underground when it’s extremely difficult to farm there? Unless you’re trading your crafts and ores for enough food to feed your entire nation, you’ll either need to discover a whole fantasy ecology (like D&D’s Underdark, or whatever’s going on with the Grot in The Dark Crystal TV series), or you’ll want to spend at least some time on the surface.

Perhaps dwarves spend the planting and harvesting seasons above ground, tending fields and so on, then retreat underground for the rest of the year. Some dwarves are left above ground to patrol the borders and guard fields and herds against predators, pests, and thieves. These surface dwarves are usually hardy loners who dislike company and often drink to get through long dull days. As these are the dwarves most people interact with most of the time, they accidentally give their species a reputation as gruff, tough warrior types. Mainstream dwarven society is actually quite gregarious, with lots of singing and dancing, and plate smashing.

Perhaps dwarves spend the planting and harvesting seasons above ground, tending fields and so on, then retreat underground for the rest of the year. Some dwarves are left above ground to patrol the borders and guard fields and herds against predators, pests, and thieves. These surface dwarves are usually hardy loners who dislike company and often drink to get through long dull days. As these are the dwarves most people interact with most of the time, they accidentally give their species a reputation as gruff, tough warrior types. Mainstream dwarven society is actually quite gregarious, with lots of singing and dancing, and plate smashing.

Why go underground at all? Mining perhaps? Or to wait out the searing heat of summer or cold of winter? Or simply because their tunnel fortresses are more secure against monsters and invaders?

6. Beautiful Dwarves

Aidan Turner’s portrayal of Kili in The Hobbit films demonstrated that dwarves don’t have to be rugged or unattractive. Why not lean into that beauty? Eyes like gems or molten metal. Hair and/or skin with a metallic or geological range of tones—burnished bronze, cool malachite, blazing gold, bright silver. Fine or strong features. Big eyes, useful for seeing underground but coincidentally appealing to humans. Melodic voices that sound like the tones of a freshly struck silver bell.

If interbreeding between dwarves and humans is possible then human populations who live near dwarven citadels may be shorter than most human ethnicities, but particularly tough, hardy and handsome.

7. Cow-Dwarves

No, not a cross between minotaurs and dwarves. Dwarves who herd cows. And ride ponies. And carry six-shooters (or pistol bows, if you really want to keep gunpowder out of your fantasy game). Because if you’re going to stick historical cultures together in your fantasy world, you are under no obligation to draw them from the same time period or geographical area.

This has the added bonus of providing an exciting new range of accents for your dwarves to speak in.

8. Heavy Metal Dwarves

They like rocks, but do they like to rock? Why not? If we’ve committed to throwing anachronistic elements into our pseudo-Medieval world (if we’re even using fake Medieval Europe as a starting point), then let’s go all out!

They like rocks, but do they like to rock? Why not? If we’ve committed to throwing anachronistic elements into our pseudo-Medieval world (if we’re even using fake Medieval Europe as a starting point), then let’s go all out!

Guitars are also called axes, great craftsmanship is required to make amps, stages, and other technological marvels. Different dwarven clans or peoples might vary from a fairly cheerful sociable culture to grim folk who paint themselves with the visage of death itself. Look to Brutal Legend and MORK BORG for inspiration here. (And why stop there? Free-spirited Jazz dwarves. Country-fried dwarves. Classical dwarves with powdered wigs and exquisitely carved instruments.)

A New Take on Dwarves

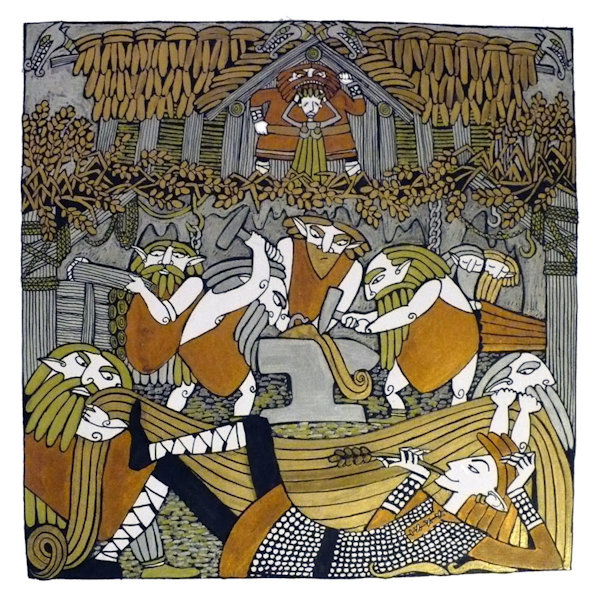

Now, for one more new take on dwarves. Let’s go back to the source material, take an idea, and see how far we can spin it out. We’re going back beyond Tolkien, to the Norse myths he drew upon.

Those mythological dwarves were so skilled at their craft that the gods themselves would bargain with them to get magical artefacts. Much of the Norse gods’ power came from these objects—Gungnir, the spear that could not miss; Mjolnir, the giant-slaying hammer; Gullinbursti, the mechanical boar that could outrun any horse that ever lived.

Those mythological dwarves were so skilled at their craft that the gods themselves would bargain with them to get magical artefacts. Much of the Norse gods’ power came from these objects—Gungnir, the spear that could not miss; Mjolnir, the giant-slaying hammer; Gullinbursti, the mechanical boar that could outrun any horse that ever lived.

What if dwarves served the gods more directly? Immortal beings of stone (similar to the Mostali), they were created to shape the world to the gods’ liking. While giants carved out mountains and seas, dwarves laid out veins of ore for the mortal races to discover; built fantastical cities and fortresses for future civilisations to inhabit; crafted artefacts and wonders for prophesied heroes to wield in ages yet undreamt; etched a thousand secrets into the fabric of the world.

Even as the mortal peoples took possession of the world, the dwarves still worked to perfect it. Until, one day, they finished their work. The gods’ will had been done.

Even as the mortal peoples took possession of the world, the dwarves still worked to perfect it. Until, one day, they finished their work. The gods’ will had been done.

The gods offered their most loyal servants their choice of rewards. The dwarves chose to experience life as mortals, each one turning to flesh so they might live out a few hundred years of freedom before their spirits were called home to the halls of the gods. They got what they wished for, the gods gave them true life and swore to give them no more commands. But this wasn’t as easy or pleasant a reward as the dwarves had anticipated. To go from immortal, unfeeling, near indestructible creatures to beings who could feel, touch, and experience emotions was immensely jarring.

Some dwarves could not cope with the change. They lost all sense of self, becoming wild and violent, or catatonic. These were locked away in great subterranean prisons, or quietly dispatched so their wounded souls could fly up to the halls of heaven where they might find peace.

The remaining dwarves split into broad philosophical factions, each one dealing with the change in their own way. These factions don’t war with each other, yet, but do squabble over social and political power. There have been riots and the occasional murder, a civil war isn’t out of the question.

The Traditionalists fell back on their original reasons for existing—crafting, building, mining. Most Traditionalists limit their own pleasures, seeking joy only in fine craftsmanship or a job well done. Extreme Traditionalists practice asceticism to an almost ludicrous degree—refusing all but the smallest amounts of food, water, and even sleep. Moderate Traditionalists may enjoy fine food or alcohol after a long day’s labour.

The Traditionalists fell back on their original reasons for existing—crafting, building, mining. Most Traditionalists limit their own pleasures, seeking joy only in fine craftsmanship or a job well done. Extreme Traditionalists practice asceticism to an almost ludicrous degree—refusing all but the smallest amounts of food, water, and even sleep. Moderate Traditionalists may enjoy fine food or alcohol after a long day’s labour.

Opposed to the Traditionalists were the Sensationalists. These dwarves sought to take full advantage of the senses their new forms granted. Sensationalists drink, feast, take drugs, and engage in all manner of sexual activity, depending on their own tastes. Think of them as a heady mix of gourmets, dilettantes and Hippies. A subsect of Sensationalists called The Bold seek the rush of adrenaline, whether through cliff-diving, white-water rafting, monster-hunting, battle, or any other dangerous activity they can find. Rumours (mostly started by Traditionalists), say some of The Bold become serial killers or blood mages, finding no greater rush than the ritualistic taking of life.

Smaller factions include:

The Artisans. Still focused on crafting things of beauty and wonder, they embrace arts that were denied to them when their flesh was stone—song, poetry, painting, textiles. Individual Artisans may lean more towards Traditionalism or Sensationalism in their personal lives.

Adopters. Sometimes called Orphans by those who dislike them. A collection of loners and small groups rather than a unified faction, these dwarves choose an existing culture and seek to join or imitate it. These adopted cultures might be ethnic, national, or tribal, but can be as specific as “the pirates of the Hidden Sea”, “the dandies of Sar Palaam’s Silk Quarter” or “the River-Runners of Northern Kull”. Some groups welcome these well-meaning imitators, others respond with disdain, anger, or even violence. If accepted, an Adopter may remain as an extremely dedicated member of that culture for the rest of their life or may grow bored and switch to a different culture every few years or decades.

Immortals. Even the promise of heaven was not enough to calm the terrors of a species of undying stone beings who found themselves trapped in fragile, fleshy shells that could only survive a few centuries at most. The majority of dwarves learned to live with their fear of death. The self-styled Immortals built their lives around it. The most striking feature of this faction is their taste in armour—whenever leaving home, Immortals wear fully articulated, bronze-washed body armour which covers them from head to toe. Their helmets are blank, curved masks, except for two small glass lenses that serve as eyeholes (even these are connected the Immortal’s eyes through mirror-lined tubes, like a periscope, so even the Immortal’s eyes remain protected by solid metal).

Immortals. Even the promise of heaven was not enough to calm the terrors of a species of undying stone beings who found themselves trapped in fragile, fleshy shells that could only survive a few centuries at most. The majority of dwarves learned to live with their fear of death. The self-styled Immortals built their lives around it. The most striking feature of this faction is their taste in armour—whenever leaving home, Immortals wear fully articulated, bronze-washed body armour which covers them from head to toe. Their helmets are blank, curved masks, except for two small glass lenses that serve as eyeholes (even these are connected the Immortal’s eyes through mirror-lined tubes, like a periscope, so even the Immortal’s eyes remain protected by solid metal).

Immortals dedicate themselves to understanding all forms of danger so it can be better avoided. They study diet and its effect on mortality. They seek to poison or otherwise wipe-out large predators. They catalogue accidents and research ways to prevent them. They are rapidly becoming world-renowned experts in medicine and healing magics. If a group of Immortals moves into an area, it is slowly transformed with safety rails, clean-swept paths, bounty notices for monsters and bandits, and so on.

This was just the first generation. Intentionally or not, the gods granted the dwarves fertility as well as mortality.

Few of the first generation of born dwarves had great childhoods. Their parents had no knowledge of child-rearing, beyond that which they could learn from the other mortal species. Children of Traditionalists faced harsh rules and a lack of understanding or empathy from their parents. Children of Sensationalists were often abandoned or neglected, or allowed to indulge in alcohol, drugs, or risk-taking behaviours that they weren’t old enough to cope with. Children of Immortals were forced to listen to long lists of all the things that could kill them, and grew up timid and wracked by nightmares.

Some of those who made it to adulthood embraced the ways of their parents. Many others rebelled and formed new sub-cultures of their own, including:

The Breakers. Breakers of rules, social conventions, heads. They enjoy brawling, loud music, piercings, extraordinary hairstyles. They dress in ragged, patched clothing, studded with nails and pins. Breakers find work as mercenaries, pirates, criminals, explorers, gladiators. They’re punks with axes and swords.

The Breakers. Breakers of rules, social conventions, heads. They enjoy brawling, loud music, piercings, extraordinary hairstyles. They dress in ragged, patched clothing, studded with nails and pins. Breakers find work as mercenaries, pirates, criminals, explorers, gladiators. They’re punks with axes and swords.

The Penitents. Believing their parents made the wrong choice, and are now being punished for that mistake, the Penitents seek to atone for this original sin of becoming flesh. The Penitents don’t agree on what this atonement will grant them—A return to the perfection of stone? A place in heaven? The peace of oblivion? But they work themselves tirelessly, abhor pleasure to a degree matched by only the most dedicated of Traditionalists and scourge themselves with self-righteous savagery.

The Doomed. Their parents gave up immortality to walk with death. Death is their constant companion and only true friend. They drink from skulls, daub their faces with corpse-paint and compose moody poems about grim subjects. Oddly, they were one of the first dwarven cultures to really embrace the idea of pets—keeping ravens, cats, wolves, and other creatures associated with death or the Underworld. (Here’s your excuse to have Heavy Metal dwarves, or Death Metal dwarves.)

The Wronged. As these dwarves see it, the gods forced dwarves to toil for countless Ages, and in return, the gods gave their faithful servants no greater reward or favour than the other mortal peoples received simply for existing. The Wronged wish to be paid in full for their parents’ labours. Several sub-sects form the Wronged. Many Wronged dwarves belong to more than one sub-sect.

- Occupiers. All those wondrous cities and citadels, lying in wait for the ungrateful mortals of the future. Why? Why should Many-Spired Yaggathrond languish unoccupied until the coming of the People of the Red Dawn in the Ninth Age? Why should the mighty brass fortress of Balefyre know no master until its great outer gate opens to the touch of the Empress-Child? What of Kelasar, the impossible city perched upon its slender needle of rock? Or Buried Oorm, with its sleeping guardian? All these places were built by dwarven hands. It is only right they now echo to the steps of dwarven feet, no matter what plans the gods had for them. Explorers, invaders, lore-seekers, they often hire mercenaries and adventurers to aid in their quests.

- Reclaimers. Much like the Occupiers, these dwarves seek to recover what their ancestors created: artefacts and objects of power. Let those who made them wield them, even if they must be stolen from the very halls of the gods. Treasure-seekers, thieves, merchants, tomb-robbers, and builders of experimental flying machines.

- Forgers. The most publicly accepted of the Wronged, they don’t wish to take anything back. Instead, they seek to learn the abandoned arts of the great dwarven mage-smiths and create new artefacts that belong only to the dwarves. Though relatively respectable, many of them have secret ties to the last and most blasphemous sub-sect of the Wronged.

- God-Hunters. It is not enough to take back what was stolen. The gods abandoned their dwarven servants to chaos, suffering, and death. The gods themselves must taste the sting of mortality. God-Hunters will learn any magic, wield any artefact and deal with any being, if it will get them one step closer to killing a god. God-Hunters make deals with dragons, alchemists, sorcerers, demons, caged titans, and disaffected giants, whoever can help them. They are absolute fanatics without conscience or restraint.

What of the gods themselves in all this? Did they intend for the dwarves to turn out this way? Are they all-knowing manipulators, anticipating and guiding even the paths of the Wronged to fulfil their mysterious designs? Are they feckless and short-sighted, acting only according to their whims and, perhaps, reaping the consequences? Were they simply trapped by their own promises? Are they uncaring? Or so unknowable they might as well be uncaring? Will they offer guidance, or new bargains to future generations of dwarves? Will they smite or curse those amongst their former servants who rebel against them?

Only time, and ink, will tell.

And there we have it, interesting fantasy dwarves. Feel free to use these ideas or reshape them to your own purposes. I bequeath them to the world.

– – –

What book has your favorite take on dwarves? How would you like to see them portrayed in media? Let us know if the comments!

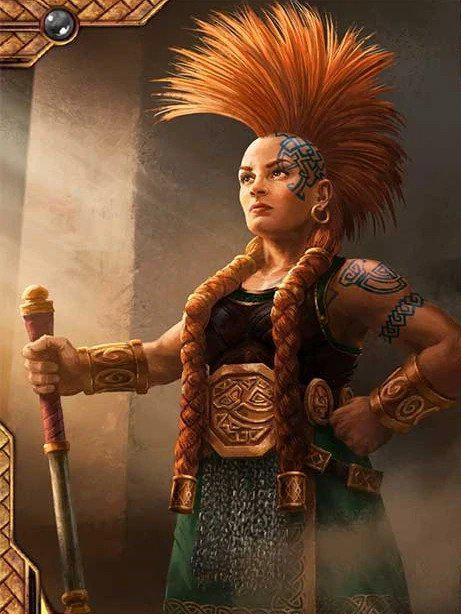

Title image by Joni Gutierrez.