Onyx Path Publishing

Onyx Path Publishing- Written by: Michael Barker, John Burke, Dixie Cochran, Rachel Cole, Matthew Dawkins, Joshua Alan Doetsch, Klara Horskjær Herbøl, Jason Inczauskis, Danielle Lauzon, Lauren Roy, Bianca Savazzi, Robert Walker, Eddy Webb, and Rachel Wilkinson

- Developed by: Matthew Dawkins

- Creative Director: Richard Thomas

- Editor: Matt Click

- Graphic Designer: Ron Thompson

- Art Director: Mike Chaney

- Interior Art: Jeff Holt, Brian LeBlanc, Ken Meyer, Jr., Andrea Payne, Aaron Reilly, Luis Sanz, and Durwin Talon

- Cover Art: Mark Kelly

They Came from! is a series of RPGs conceived by Matthew Dawkins and published by Onyx Path. It began with They Came from Beneath the Sea!, the game of 1950s sci-fi B-Movies.

Beneath the Sea! was hardly the only game to explore the worlds of films and TV from the 20th Century (Nitrate City, Straight to VHS), but it was fresh and fun and leaned very hard into the idea of the world being a film set.

Now They Came from! attempts its difficult second album, moving into the 1970s and exploring supernatural horrors like demons, vampires, werewolves, ghosts, and slashers, instead of bug-eyed aliens and atomic robots.

It’s still comedy horror. But while Beneath the Sea! was a farce, complete with oddball monsters and dumb plots, Beyond the Grave! is a portentous setting that generates humour by taking itself too seriously—classically trained actors chew scenery and necks with equal dedication while litres of fake blood pour from cardboard walls.

It’s still comedy horror. But while Beneath the Sea! was a farce, complete with oddball monsters and dumb plots, Beyond the Grave! is a portentous setting that generates humour by taking itself too seriously—classically trained actors chew scenery and necks with equal dedication while litres of fake blood pour from cardboard walls.

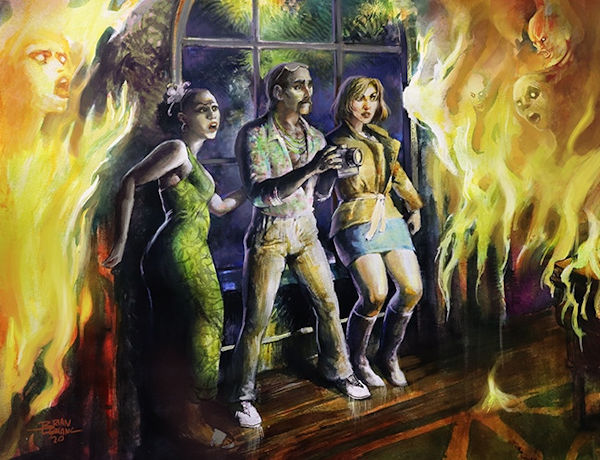

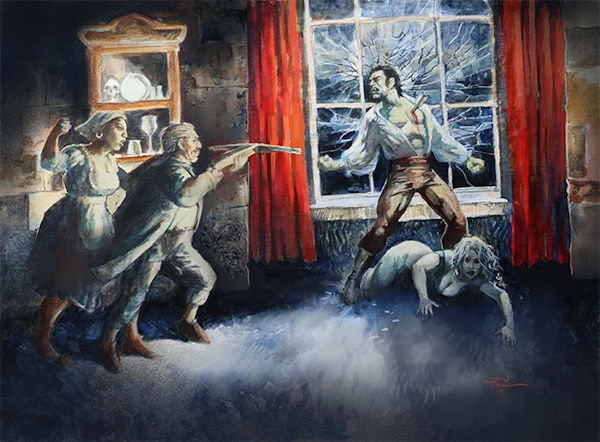

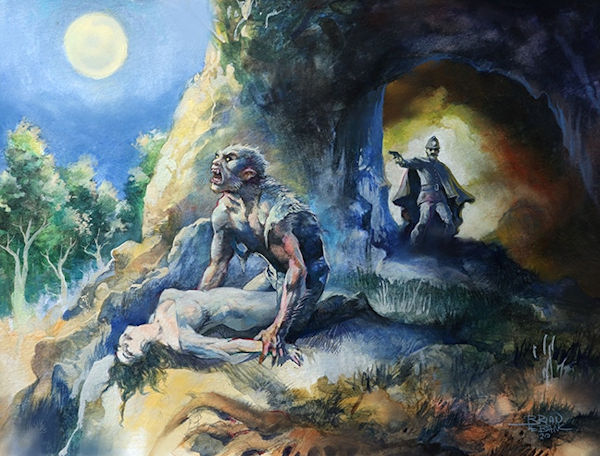

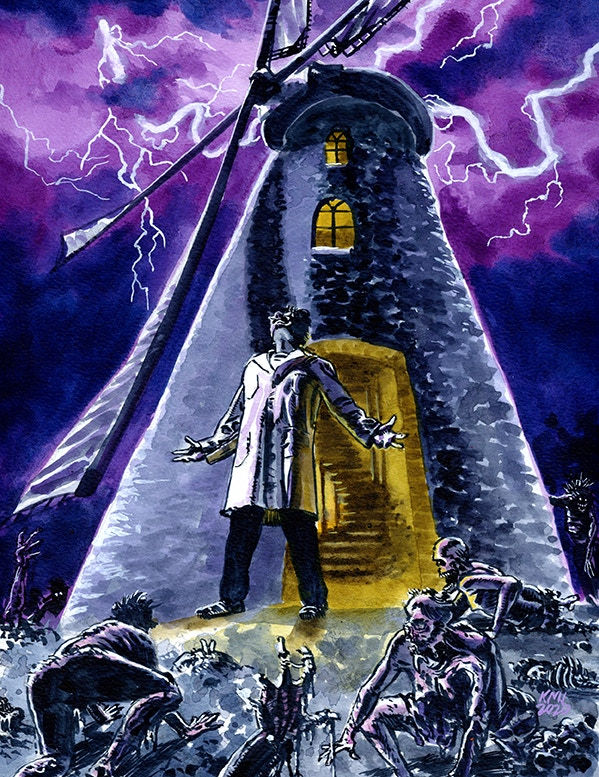

The art is plentiful and builds up this new campy aesthetic nicely, ranging from dark, gritty comic-book style scenes to bright but washed-out watercolours. Then there are the weird and luridly colourful posters for movies that might have existed. (These are really quite special, and unique for an RPG book in my experience, though I’m sure someone somewhere has done something similar.) Monsters and heroes pose dramatically, battle each other with savage fury, and show a surprising amount of skin (because 1970s horror was often as much about titillation as it was about fear).

Okay, first problem. There aren’t any other RPGs (to my knowledge) about mind-controlling seaweed and were-lobsters. But there are tons of RPGs about vampires, werewolves and serial killers. (Onyx Path has made some of them.) Even cinematic representations of horror in RPGs aren’t that rare—Dread, Dead of Night, All Flesh Must Be Eaten. So, Beyond the Grave! not only has to live up to the splash made by its predecessor, but also carve out a bloody niche for itself amongst other games of cinematic supernatural horror. How does it do that?

Well, intentional horror-comedy is a lot rarer than horror in RPGs. And Dawkins has just the sort of dry, but goofy, humour that lends itself well to that combination.

This book is also not at all subtle about the film aspects of the setting. The game doesn’t just reward players for sending their characters into the creepy basement; it allows them to lose footage when the encounter with the basement-dwelling gargoyle goes badly and skip to a safer scene, or punch their way through the basement’s plyboard ceiling, or take advantage of the fact that this “basement” set still has a secret door from when it was the set of The Room that Sobbed Blood.

Beyond the Grave! doesn’t shy away from the classics either. You can invent your own demon or vampire, sure. But you can also pit your players against Dracula, Frankenstein’s Monster or THE DEVIL HIMSELF. Never mind that Dracula was killed over a hundred years ago, now he’s back and running a community blood drive at his stately home in downtown Manhattan.

Then there are the dual time periods. A classic game of Beyond the Grave! takes place in both the 1970s and the Victorian era, with players taking on the role of their characters’ descendants or ancestors. (Or reincarnations or inexplicable lookalikes). Did you wander into a creepy castle with a dark past? Instead of getting all the exposition about why the castle is haunted from chatty ghosts, informative butlers and highly specific diary entries, would you like to play through that backstory yourself? This is the game for you!

Other notes. Onyx Path do love to include in-universe fiction in their games, and Beyond the Grave! is no exception—The Curse of Casa Clifftop kicks things off, with other offerings including Imps!, Satan’s Bloody Lust and She Walked on Eight Legs! In this case I found these stories quite fun to read and very helpful to my understanding of the mood for the game. (And mood is incredibly important to Beyond the Grave!)

The movie posters are a nice source of mood, atmosphere and plot hooks too.

Chapter 1. Introduction

“They Came from Beyond the Grave! is a game unashamed of its influences. You absolutely should pull plots from the Hammer horror and Amicus movies you love.”

The writers set the tone of the book immediately: wry, erudite, conversational. It feels like the game is being explained by a stately older person wearing a tweed jacket and sitting in a winged leather armchair beside a roaring hearth. Possibly while holding a glass of brandy in one hand.

Only once you’ve been drawn in by the style of writing do they circle back to explain the basics of the setting and system. Including the usual information about what an RPG actually is and how to play one. Horror, comedy and melodrama are emphasised as the key elements of Beyond the Grave!

We get an example of play, which I really appreciate, it’s the perfect way to help new roleplayers understand what’s going on.

The intro also includes a long list of horror films that can be used as inspiration for Beyond the Grave! Not just the titles, but mini reviews and explanations of why each film is important, fun or interesting. (Vincent Price features heavily.) The writers’ passion for their subject really shone through here, and this section really helped to establish exactly what this game is about in my mind.

I also liked the brief breakdown of all the chapters and what they’re about. Very handy!

Chapter Two. Archetypes

Archetypes are sort of like character classes—they help to define a character’s abilities, outlook and lifestyle. To put it another way, they define what role the character plays in the film; are they the grizzled veteran, the fusty academic or the confused (but ultimately heroic) housewife? Certain powers, such as Tropes and Trademarks, are listed by Archetype. Like its predecessor, Beyond the Grave! presents five Archetypes—Dupe, Hunter, Mystic, Professor and Raconteur.

The Dupe is an interesting character type because they start out as mundane, ordinary, even dull people. It’s unusual for an RPG to have a class or archetype based around mediocrity. Even compared to the plucky Everyman from Beneath the Sea!, the Dupe is hapless and seemingly helpless. They are unlucky enough to stumble into the plot and simultaneously lucky enough to probably survive it. (One of their Tropes lets them automatically escape a scene if they wish to.) They can also be charming, well connected and surprisingly feisty.

Hunters are your Van Helsing types—people who understand something about the supernatural and have dedicated themselves to rooting it out and destroying it. They specialise in tracking specific types of monsters and knowing their weaknesses. They rarely have sympathy for monsters and may clash with more soft-hearted or inquisitive Archetypes. These characters are often lone wolves or inclined to work only with bands of like-minded hunters. But the writers provide a good reason for Hunters to team up with other Archetypes—they struggle to defeat opponents with high social skills, or creatures such as ghosts or demons who can possess innocents.

The Mystic is not a magic user in the D&D sense; they don’t have lists of spells. Instead, they are in touch with the supernatural, whether through psychic visions, faith, or their own delusions. They are fortune-tellers, palm-readers, psychics, nuns, priests, and occultists. The Mystic is often the character most sympathetic to monsters, particularly the spirits of the dead. Nonetheless, they are very good at gaining information in unconventional ways, such as through psychic object reading or digging strange lore out of crumbling grimoires.

The Professor is the brains of the outfit. They don’t have to have a university degree, but they do need to be passionate about their chosen topic of study. They might be a scientist or inventor, a folklorist or a fitness instructor with a fascination for wildlife. Their Tropes mainly focus on research, knowledge, and applying science to the supernatural, though one allows them to use ‘rational debate’ to argue any single character into an exasperated rage.

The Raconteur might be a detective, journalist, explorer or celebrity, but they are almost always flamboyant and wordy. They are good at picking up clues by reading a crime scene or seeing through a witness’s lies, but also tend to excel in social situations, always dressing the part and relishing attention.

Each Archetype comes with a list of one-line example characters e.g. “The snobbish actor with a horrible secret behind his makeup.” “The swami who saw a half-man, half -wolf in the courtyard a couple of nights ago.” “The stay-at-home mom whose daughter has been missing for two years.” This is an excellent addition, which illustrates how broad the Archetypes can be.

Chapter Three. Character Creation

The Storypath System has a fairly involved character creation process, and Beyond the Grave! still has a few too many different character powers for my comfort. But it’s all laid out well here, with a helpful breakdown at the beginning, links to referenced pages and two examples of character creation. (One runs alongside the rules information, the other is given at the end, so you can see the whole process put together.) I really love that style of explaining character creation and intend to steal it if I ever write another RPG.

You pick three Paths that define your character—Archetype, Origin, and Dark Agenda. Origin is what you’d expect, the character’s beginnings. Dark Agenda is the character’s motivation for getting involved in supernatural events—it doesn’t have to be sinister, but the sample Agendas include Failed Experiment, Forbidden Love and Cult Leader.

This modular approach to character creation really helps to spark creativity. Some Origins and Agendas are obvious fits for certain Archetypes—it makes sense that a Hunter would be motivated by revenge. But why is the Blue-Blooded Professor seeking revenge? And what Failed Experiment did the Criminal Dupe get herself mixed up with?

You assign Skills to your Paths, and get points to spend on them, then you get some more points to spend on any Skills you like. Attributes are broken down by Social, Mental and Physical (with three Attributes in each category), and you rank these Arenas as first, second and third, assigning points accordingly. You get extra Attribute points in the three Attributes that fit your Favoured Approach.

You also pick out:

- Tropes: minor powers based on the expectations of the genre and your Archetype. (Described above, in the Archetype descriptions.)

- Trademarks: phrases you can mention to get bonus dice when rolling a specific Skill. These are arguably the most powerful character abilities, because if you succeed a roll while using a Trademark, you can take Directorial Control of the Scene and change some details about it. Examples include “Darling, you look ravishing tonight”, “This is both improbable and impossible”, and “Not to worry, I know the host”.

- Quips: catchphrases you can say in character to get bonus dice, as long as the rest of the table find them funny. Quips get more powerful the more you use them, encouraging players to repeat ‘iconic’ lines and to cram their catchphrases into any situation. (I must admit, almost all the Trademarks and Tropes could be recycled as Quips, which can make it a bit tricky to keep track of which ability is which.)

- Connections: characters and groups who will help the character, as long as they don’t ask too much or fail to pay back favours in kind. These include access to things like labs, exclusive clubs or hideouts. A character can have up to nine Connections, with three per Path. Unlike Beneath the Sea!, Beyond the Grave! explicitly states you should just make three Connections to start with and fill in others later, which I think is a much better way of doing things. I’ve reviewed several Storypath books now, and this one is absolutely the best so far at explaining Connections and how to use them.

- Relationships with other Player Characters: These can be positive or negative, either way they grant bonus dice if you play up to them. Beyond the Grave! adds a new type of Relationship: Fated Bonds. These are romances, enmities or soul-deep friendships that last beyond time and death and grant special abilities called “Fated Tropes”. This allows Players to e.g., play out a romance between their Victorian characters, which are continued by their reincarnated selves in the 1970s.

- The character’s initial Aspirations: things you want to happen to the character, regardless of whether or not the character themself wants those things to happen. Short term Aspirations could be “kiss a cannibal”, “dispatch a minion of the DEVIL HIMSELF”, or “study a sample of ectoplasm”. Long term Aspirations could be “break the curse on my family” or “kill every last werewolf in existence”.

The authors provide some nice, thoughtful descriptions of how to imagine your character concepts, aspirations and paths, and encourage you to try new angles on old tropes. “What if the werewolf is the resident of an asylum, let loose on every full moon by the chief medical director for some nefarious purpose called SCIENCE!”

The authors provide some nice, thoughtful descriptions of how to imagine your character concepts, aspirations and paths, and encourage you to try new angles on old tropes. “What if the werewolf is the resident of an asylum, let loose on every full moon by the chief medical director for some nefarious purpose called SCIENCE!”

Some material in this chapter is really just stuff from Beneath the Sea! with a new coat of paint on it. (The authors aren’t making any secret of that.) The Professor, Dupe and Raconteur are clear matches to the Scientist, Everyman and Mouth, though with their focus shifted to a different time period and genre. A few Tropes have been lifted straight from the previous game. Many others are new, however, and the Hunter and Mystic aren’t really analogues to the Survivor or the G-Man.

Ultimately, all the Archetypes are fun and offer lots of possibilities. So, I’m happy.

Chapter Four. Skills and Attributes

These are the same as Beneath the Sea!, though explained in the context of Beyond the Grave!’s gothic horror setting. E.g., “Command allows characters to scream “destroy it!” from the epicentre of a fray and be sure their companions will smash the glowing amulet against an ancient stone dais, sending the abhorrent coven of warlocks to the great beyond once and for all.”

This makes the chapter quite entertaining to read, as well as informative.

Each Skill and Attribute comes with three very helpful example Trademarks and explanations of what they mean and how they might be used. The authors are building on the success of the first game and have clearly worked hard to refine the layout and content of powers and abilities to make them easier to understand.

Chapter Five. System

My comments on the Storypath System from previous reviews still apply to They Came from Beyond the Grave! It’s a nice, sinewy system that covers most bases with its core system of building a dice pool of D10s and counting the number of Successes rolled. More difficult actions require more than one Success. Dangerous or risky actions come with Complications, which must be bought off with Successes or suffered. A Complication could be anything from a jagged barbed wire fence that could injure you as you try to climb over it, to an enemy catching you off guard with an ambush.

Though straightforward at its heart, They Came from! has a lot of extra bells and whistles to keep up with—Stunts, Cinematics, Tropes, Trademarks, Quips, Connections, Atmosphere, Attitude, Tags, Conditions.

Still, all of this is explained in a pleasant, readable tone, as though told to us by a kindly but faintly menacing uncle on a stormy night.

Onyx Path’s writers remain socially responsible too.

“Influence isn’t mind control. A target’s Player chooses whether or not to accept the result of the roll. It’s generally advised to accept the roll and adjust the character’s actions accordingly, but if the story would suffer or anyone at the table would be made uncomfortable by doing so, ignore it. The story and your friends are more important than any dice roll.”

The rules explanations are backed up with copious examples, breakdowns and tables, which is all extremely helpful. And it always comes back to films. Scenes are broken down into Investigation, Action and Drama, with explanations of how to run them effectively, as well as descriptions of the rules.

The first aid rules are particularly clever. And the, possibly new, inclusion of Scene Combat makes a lot of sense—these are rules for playing out a combat scene against e.g. a swarm of mindless undead or disposable cultists with just a couple of dice rolls.

Fated Bonds are expanded here, they grant new Stunts (sort of special moves you purchase with extra Successes). Perhaps you can always track down the other half of your Fated Bond, or maybe you can defy physics to throw yourself into the path of a blow meant for them. All fun stuff.

I must admit though, I still don’t understand how NPC dice pools work in Storypath. I understand the principles, but I can never match up the bestiary entries with the suggested pools in the example tables.

Chapter Six. Cinematic Powers

This chapter delves further into Cinematics, Stunts, Quips, and the Haunted Condition.

“Cinematics are powers the Players use to influence and edit the course of the game, as if taking on the role of Director…Crucially, characters are typically unaware of these powers being used.”

An iconic part of the They Came from! Line, Cinematics are a ton of fun. Some are recycled from the previous game, but many are new, drawing on the overblown horror tropes and poor budgets of 1970s horror films. Your character could get so covered in blood the villains assume they must be dead. A musical montage could grant bonuses to extended rolls. The actor playing the monster might have to run out of the Scene early with stomach cramps because craft services are only serving up expired hot dogs. Perhaps you get bonuses to a social roll because your character’s actor is determined to give a bravura performance, no matter how crap the film around them is. You could initiate a romantic Scene no matter the circumstances, slip out of shot and return dressed as a minion of the villain or shudder as a perfectly timed crash of thunder emphasises the terrible revelation you’ve just shared with your companions.

Haunted is a special Condition. It is the equivalent of Encountered from They Came from Beneath the Sea! Unlike Encountered, which unlocks all Encountered Stunts, Haunted grants one specific ability, such as bestial claws, and may be detrimental as much as helpful. You can lose or get rid of Haunted Conditions, unlike Encountered. This is easier to keep track of than the Beneath the Sea! version and does seem fun.

Stunts in general have been reorganised and are now easier to follow. Each Skill gets three associated Stunts, so you know exactly when to use them. These Stunts cover everything from replicating poisons, to running monsters down in your car, to creating an antidote to lycanthropy to influencing an NPC’s actions even when they’re nowhere near you.

Archetype Stunts make a return, allowing each class to demonstrate their unique capabilities. They have been cut down to just three per Archetype. Mystics can manage actual magical effects. Dupes can experience a sudden burst of courage. And so on.

Quips are also a little more straightforward in this game and are well explained. They are divided by Archetype, though you don’t have to pick them from your character’s Archetype list. Maybe it’s just my personal sense of humour, but I vibed more with the Quips in Beyond the Grave! than the ones from Beneath the Sea!

There are dozens of Quips. Here’s a tiny sample:

- “Don’t touch me with your awful hands!”

- “We call them the undead.”

- “It’s an orgy of horror!”

- “Behind this sweet mask of purity, there exists a twisted mind.”

- “Nonsense! Twaddle! This is no answer!”

Overall, there are just as many Cinematic Powers in this book as in the first one, but they’ve been tidied up and are that much easier to grasp.

Chapter Seven. Monsters

“Abaddon is a fell being, wreathed in a cloak of midnight black, masking its demonic aspect behind a shimmering helm, fronted with a snarling, obsidian faceplate.”

“Abaddon rides a black charger with burning, red eyes, named Buhtakupp.”

This bestiary consists of classic horror monsters, and a couple of odder offerings. They all get fulsome descriptions and a plot hook each for both the Victorian era and the 1970s.

There a few less entries than Beneath the Sea! had, which is sad. It’s also worth noting that this bestiary is more concerned with behaviour and campaign use than with biology. For example, the Feral Vampire, Noble Vampire and Dracula are all undead bloodsuckers, but they have different goals, behaviours and general capabilities, so they get a different write-up. The key point being a film about a sophisticated socialite who happens to feed on his lovers, would be quite different to a film about a mud-smeared monster that jumps people in alleys and drags them back to her underground lair to rip them apart and feast on the remains. (The Bride of Dracula is actually a different creature, a bat-like demi-vampire that wears a seductive human disguise, quite reminiscent of the Red Court vampires from The Dresden Files.)

Similarly, the Stalking Killer and Slasher are both human serial killers, but one is very stealthy, and the other is very hard to kill.

There are ghosts, ghost-ships, haunted houses and malevolent ghost amalgamations. Each has a different role or motivation, despite being essentially the spirits of the dead. I understand the approach, but it does mean this book doesn’t quite have the wow factor of Beneath the Sea!, where you could read the name of almost any monster entry and make your friends crack up laughing or demand to know what this game was.

Now, there’s still some fun stuff in this chapter. As I mentioned up front, the authors didn’t shy away from big names! Joining Dracula are:

- Frankenstein’s Monster: Yes, that one.

- Abbadon, the Locust King: An apocalyptic demon lord who fights with a flaming sword, a horn of murderous rage and a swarm of flesh-ripping locusts! His picture is particularly awesome.

- The Masque of the Red Death: A creation of Poe, this being is a humanoid manifestation of plague.

- THE DEVIL HIMSELF: Who must always be capitalised and who can manifest in different forms of varying power, all inhumanly cunning and hungry for souls. THE DEVIL HIMSELF can be used as the catalyst for an adventure, not just serving as an antagonist, but actively pushing Player Characters into the plot by forcing them to relive their nightmares, face their sins or battle against wicked temptations.

The other creatures also get interesting and evocative descriptions. A lot of this material could be ported straight over into a serious horror game without any trouble.

“They are floating, hulking tangles of faces, with stretched, taut, sneering mouths lined with misshapen teeth and screaming in eternal agony. Rows of weeping, malformed eyes line every inch of their bulk, allowing them to see in all directions.”

Human villains are plentiful—Demon Worshippers, Twisted Scientists, Witches and Warlocks. And there are some stranger creatures, like ratmen, hypnotic giant spiders and the horrid, but brilliant, Wax Palace.

One more thing that stood out to me: Zombies, a horror and dark fantasy staple. Possibly the most boring monster in a modern writer’s arsenal. I have railed against them plenty of times before. But I was impressed by their depiction here. They’re not just low level undead, they are a horror film staple—scary because they gather in numbers.

In Beyond the Grave!, Zombies effectively multiply—at the end of a Round if there are any Zombies still undead, then an equal number of Zombies join them at the start of the next Round. So, you either wipe a group of Zombies out very quickly or find yourself forced to retreat or take shelter, just like in the films. All this is accomplished without worrying about how the Zombie curse spreads or if Player Characters can be infected. It’s a very simple, but very clever rule.

Overall, still a pretty good, thematic, bestiary that caters very well to the game it was designed for.

Chapter Eight. The Director’s Chair

“Everything has a dreamlike quality, adjacent too but not quite touching reality—from the too-bright blood, to dry ice fog flowing through studio forests.”

“Be advised that there exists a special circle in Hell for Directors who use jump scares more than sparingly.”

“Embrace anti-climax. Hug the wheezing, flatulent little monster close.”

The writers have a clear vision of the game and communicate it with that same dry conversational tone they’ve used throughout. It makes for a GM’s Guide chapter I didn’t want to skip through. Quite the achievement!

The chapter is full of reassuring, practical advice about managing your table, creating atmosphere, keeping everyone safe and happy. Key points are you should make failure fun and that player agency is very important.

A few weird and wonderful game structures I’ve never seen before are introduced. The Portmanteau—multiple stories connected in some way e.g. strangers in a diner forced to share stories by THE DEVIL HIMSELF. Players in this kind of game can create and alter story prompts amongst themselves. It’s not quite improv or a GM-less game, but it’s at least nodding to them.

Or you could forget films and present the campaign as a cheap soap opera or long running TV series in the style of Dark Shadows. Swap characters in and out, use the same corny intro at the start of each game. Focus on a single town or location. Allow the plot to move slowly, meandering back and forth over the same conversations and confrontations. (I’m not sure about that last part, but it’s a choice.)

Interesting and useful, even experienced GMs may benefit from reading through this chapter.

Chapter Nine. This Horrible World

This chapter is somewhat experimental. Whereas Beneath the Sea!, like most Onyx Path products, had a rich and detailed setting, Beyond the Grave! leans into the idea of being a film and states there is no reality beyond this scene, or set. Don’t worry about how the government or press are reacting to tales of vampires, ghost ships or mesmeric spiders. Don’t worry about who’s at war with who or what is socially acceptable for the time. You are in a mall and there’s a serial killer on the loose, that’s all that matters.

After a couple of paragraphs each introducing the 1970s (paisley, grooviness, nightmarish blends of science and superstition) and the Victorian Era (overwrought, dark, cobwebby), the bulk of the chapter is a series of locations, each broken down into specific sets, all complete with mini prompts.

“Anything can happen in a dark wood, but in this looming, loamy place, the shadows themselves take on a sort of life, flickering and shifting ominously in the muted moonlight. There’s a howl in the distance, and as your foot cracks a dead branch, crows scatter from the trees, cawing raucously. An animal—one hopes—rustles in the crunch of undergrowth, and a chill cuts through the air when what little moon there is disappears behind thickening clouds.”

“Emergency Room: Blood from a strange wound pools sticky on the floor where the patient was wheeled in, and busy nurses struggle to triage everyone waiting. Someone vomits on the floor; a patient starts sniffing, then licking up the blood; nurses scream from behind closed doors.”

Locations also come with sample Complications and Enhancements e.g., using a light source in this creepy abandoned manor may draw unwanted attention from passing people (or things that look like people).

It’s an almost OSR style approach and is clearly intended to get the most “game juice” (prompts, plot seeds, inspiration) out of each page. Fair play to the writers for trying something a bit different, it’s a perfectly valid way of writing a setting that many people will appreciate, and it fits the conceit of being a film.

Personally, having spent a lot of time reading through RPG books where the setting is a few lines of item descriptions, or a table for generating unfortunate trousers or a line about the empty-eyed Crimson Tigers of Moonbase Hotel or what-have-you, I’ve decided I prefer a nice, filled out setting. So I would have enjoyed a little more detail on the implied setting of Beyond the Grave!, because it’s a very cool setting.

In fairness, if the game was only set in the Victorian Era, I probably wouldn’t need anything else. I’m already steeped in gothic Victoriana, so the Victorian sets absolutely caught my imagination. The 70s though? That shadowy, sharp-collared decade between the bright, Hippy-Hippy 60s and the greedy, power dressing 80s? Well, I’ve seen Anchorman, and Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, that’s about it. And I imagine that quite a lot of people in the 70s didn’t run around hallucinating pterodactyls or shouting about whales’ unmentionables. So, I could have used more info on the culture, the people, the events and the general vibe of the 70s.

If you’re familiar with both time periods (or the films this game is based on), you won’t have any trouble getting the most out of this chapter. If not, you might want to watch at least a few of the films listed in Chapter One, to get a better idea of the setting. Still, dig through this chapter and you won’t be short of creepy descriptions or interesting plot seeds. It’s all beautifully written, drenched in atmosphere and ripe with seething horror. And as long as you can keep your merry band of actors/players/characters confined to the on-set locations, you’ll be fine!

There is one other very interesting idea at the end of the chapter: Lens Filters. These are themes or conditions that alter locations. For example, this location could have been rewired into a death maze by a murderer, or the characters could be exploring it after hours, or it might only look like a cinema and really, it’s part of a hell dimension. There’s even a Christmas Special Filter! Each Filter comes with three features, such as excessive booze, eternal fires, dream logic or razor wire. Lots of scope for interesting and horrible adventures here!

Chapter Ten. Scenarios

We get two full scenarios for the price of one here. Which is excellent, I love an RPG that shows you more than one way to play and gives you full details in its starting adventures!

Die for the Devil

This is a sandbox scenario where the Player Characters wander into an isolated rural community and get pulled into a wicked supernatural plot. The villains’ plans will progress as the players do their thing, which is always good. The adventure is complete with dark secrets, deviltry, weird visions, stormy weather and a flashback scene where Victorian characters must resist or participate in a witch-burning. It may be difficult to overcome the final confrontation, but certain actions taken throughout the scenario (including during the flashback), can grant the Player Characters bonuses at the end, which really justifies and rewards all of the “wandering around and messing with stuff” players are inclined to do in a sandbox game.

The scenario itself is well written and funny, like the rest of the book. One quibble is it could have done with a little description at the start, explaining what the villains are up to. It’s hard enough to set up a plot and keep it running while the players blunder through it, don’t make the GM have to do detective work on what is actually happening as well!

The Masque of the Hideous Heart

This is a portmanteau style scenario based on all the films that are based on Edgar Allen Poe’s stories. The core story is the “Tell-Tale Heart” reimagined as a supernatural menace, but just about any Poe character or situation could be pulled into the narrative. The adventure begins in a police station in the 70s, where the PCs have been gathered by a detective to discuss a series of supernatural murders their Victorian ancestors investigated. The bulk of the action is set in the Victorian Era, but the 70s characters can interject their thoughts, allowing players to inject fresh ideas and even whole plot arcs into the narrative.

From a Victorian police station full of befuddled officers and chatty criminals, to the rainswept streets, to a lavishly, wickedly, decadent party full of curious, malevolent guests, this adventure promises tons of ghoulish fun! I must admit I love this Poe-etic playground.

(And this adventure does have a good up-front explanation of the villain, their goals and abilities, as well as the themes of the adventure.)

At the time of writing, I have run the first part of this adventure with a group of friends, and we had a great time. That’s as much a testament to the game as a whole as it is to this specific scenario. My players were all excited about the character options on offer and have been having a blast getting into character. They really enjoyed Quips (using them more often than they rolled, in some cases). They really liked the conceit of playing through a film, with—scenes cutting back and forth awkwardly, a side character whose lines have clearly been cut down heavily, a very unconvincing cat puppet, and a surprisingly breathy and underdressed police officer.

At the time of writing, I have run the first part of this adventure with a group of friends, and we had a great time. That’s as much a testament to the game as a whole as it is to this specific scenario. My players were all excited about the character options on offer and have been having a blast getting into character. They really enjoyed Quips (using them more often than they rolled, in some cases). They really liked the conceit of playing through a film, with—scenes cutting back and forth awkwardly, a side character whose lines have clearly been cut down heavily, a very unconvincing cat puppet, and a surprisingly breathy and underdressed police officer.

My players engaged less with Tropes and Trademarks, hoarding them against a time of need, but it’s early days yet.

Conclusion

My usual quibbles about design and content choices aside (I always have quibbles), I liked reading this game and I really liked running it. Something about the combination of gothic melodrama and the conceit of a low budget movie just lets people cut loose and have fun. I’ve had to put my game of The Masque of the Hideous Heart on hiatus while I wrestled with a dose of Covid, but I’m itching to get my players back around a table and play through the next session.

It’s fun and funny, gruesome and gory, over-acted and overblown. It has a different flavour and style to Beneath the Sea!, which justifies forking out the cash for a new iteration of the original formula.

To get the most of out of this game, you should probably watch a few 1970’s horror films first, or at least some clips of them. (Ideally, clips with Vincent Price in them.) But whether or not you’re familiar with the source material, I heartily recommend buying this game and jumping headfirst into a world of spooky scares and splattery special effects!

Disclaimer: I received a digital copy of this book in return for an honest review.