A couple of days ago, Elspeth Cooper guest blogged at Bookworm Blues about a running theme in Songs of the Earth, the first in a fantasy series that has been received very kindly by reviewers here at fantasy faction—not only that, but Songs made it to the shortlist stage of the David Gemmell Legend Award voting. That theme is disability.

A couple of days ago, Elspeth Cooper guest blogged at Bookworm Blues about a running theme in Songs of the Earth, the first in a fantasy series that has been received very kindly by reviewers here at fantasy faction—not only that, but Songs made it to the shortlist stage of the David Gemmell Legend Award voting. That theme is disability.

Cooper herself says in the post that “genre heroes and heroines have a tendency to be clean-limbed and strong” (she expands further; go read the post here and you won’t be disappointed!). The problem is; she’s entirely right. Heroes and heroines might be expanding in race, gender, colour and sexual preference, but one thing that is still stuck running backwards, is physical capability and disfigurement.

When was the last time a character had a god-awful scar that a) didn’t automatically make them a badass (like Cooper says), b) wasn’t either a sub-character, going to get killed off, or wasn’t a villain, or c) can’t simply be hidden. A visible scar, or an obvious or chronic illness (mental or otherwise), or something that detracts from the notion of “able-bodied perfection” as far as characters go.

Cooper might not have deliberately touched on this much-neglected area of character, but it’s certainly provided food for thought. A quick wracking of my brain thought up a handful of characters who tote their own disabilities:

Chris Evans, in his military fantasy trilogy, the Iron Elves gives us Alwyn, who is horrifically-sighted and loses a leg through injury at some point during the story. If we delve a little deeper with Ally’s character, his development towards the latter part of the series shows that he might just be a little “insane” (naturally, there’s a context within the story) to boot. A physical and a mental defect. However, does it make a difference that Ally is a soldier? Surely soldiers are expected to pick up defects here and there, and it doesn’t really strike a chord as anything special. Maybe. But then if we look at Konowa, with his lopped-off ear-tip, shorn when he was a child to remove the Shadow Monarch’s mark, it deepens a little. Even with hair drawn back in a standard issue military queue, there’s little Konowa—and elf—can do to hide his missing tip. His being an elf is all the more poignant.

Chris Evans, in his military fantasy trilogy, the Iron Elves gives us Alwyn, who is horrifically-sighted and loses a leg through injury at some point during the story. If we delve a little deeper with Ally’s character, his development towards the latter part of the series shows that he might just be a little “insane” (naturally, there’s a context within the story) to boot. A physical and a mental defect. However, does it make a difference that Ally is a soldier? Surely soldiers are expected to pick up defects here and there, and it doesn’t really strike a chord as anything special. Maybe. But then if we look at Konowa, with his lopped-off ear-tip, shorn when he was a child to remove the Shadow Monarch’s mark, it deepens a little. Even with hair drawn back in a standard issue military queue, there’s little Konowa—and elf—can do to hide his missing tip. His being an elf is all the more poignant.

Another character with something of a disability is Malum from Legends of the Red Sun (Mark Charan Newton). Not only is he a half-vampire (not properly changed), but he is also impotent. It’s not technically a disability, but it’s a big deal for us chaps, and when added to the fact that Malum is an extremely strong and violent-natured character, it can definitely be considered a physical “defect” for his character. Malum is a leader, a fighter, a hard-ass, and he’s impotent. It’s a pretty unique move on Newton’s part, and along with Malum’s other character details it gives him an inner rage that fuels his every decision.

![Newton-CityOfRuinPBUK[3] City of Ruin (cover)](http://fantasy-faction.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/Newton-CityOfRuinPBUK3-198x300.jpg) Sticking with Newton—and for something a big bigger this time—we have Nanzi. If Nanzi isn’t “disabled”, I don’t know what she is. Oh, she’s a fantastically strong woman who is reliant on her man, but independent from him when she pulls away to her own space, as well as being an ultimately good-natured character despite the obvious flaws in her character’s decisions, but she’s also half spider. Nanzi, having barely survived an accident, has been surgically aided and is pretty much a half spider, complete with spider legs, silk sac, and general arachnid-ness. Nanzi is far, far from being perfect—and that’s the point.

Sticking with Newton—and for something a big bigger this time—we have Nanzi. If Nanzi isn’t “disabled”, I don’t know what she is. Oh, she’s a fantastically strong woman who is reliant on her man, but independent from him when she pulls away to her own space, as well as being an ultimately good-natured character despite the obvious flaws in her character’s decisions, but she’s also half spider. Nanzi, having barely survived an accident, has been surgically aided and is pretty much a half spider, complete with spider legs, silk sac, and general arachnid-ness. Nanzi is far, far from being perfect—and that’s the point.

More characters should be imperfect, whether to a small degree, or to a massively blatant degree that no amount of preening or powder can hide. That’s not to say that we do away with the rest of our heroes—that would be swinging entirely in the opposite direction, and render the idea of introducing the normality that differences in colour, sexuality, race, gender and physical appearance and capability completely pointless.

There’s an even balance between perfect and imperfect and usually, striking somewhere in the middle, or middle-left or –right is best. Not all of Cooper’s characters are deliberately sick or disabled, it’s just their character and who they are. Ansel is old, Gair gets branded as a punishment, Aysha is crippled, and Darin simply is a diabetic.

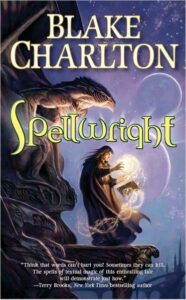

Nicodemus Weal in Blake Charlton’s Spellwright trilogy is essentially dyslexic and later on, Francesca DeVega is essentially deaf. Disabilities, both, but subtle and where the story is entirely dependent on Nicodemus’, the story could plod on regardless of whether Francesca ever became deaf or not. Sometimes disabilities are there from the get-go, others are acquired. A story can, should it wish, rely entirely on a disability, or it could carry on with nary a nod of acknowledgement.

Nicodemus Weal in Blake Charlton’s Spellwright trilogy is essentially dyslexic and later on, Francesca DeVega is essentially deaf. Disabilities, both, but subtle and where the story is entirely dependent on Nicodemus’, the story could plod on regardless of whether Francesca ever became deaf or not. Sometimes disabilities are there from the get-go, others are acquired. A story can, should it wish, rely entirely on a disability, or it could carry on with nary a nod of acknowledgement.

Harry in the Dresden Files procures a very, severely injured hand after an ill thought out defence that backfires (*cough* literally), and this has consequences, both mental and physical, that carry through into subsequent books. Not to mention that, for a time, Harry’s friends wonder if he’s mentally ill when he starts talking to himself, when in fact he’s interacting with an apparition that appears to only him. Then he acquires a scar that he cannot hide, and isn’t particularly flattering or “badass”, since Butcher never really wrote the character that way—Harry might be cool, but he’s more wiseass than badass, for sure.

Essentially, characters can pick up imperfections as they go along, and while they can just as easily not do, it adds a layer of realism and believability to whatever they’ve been through. To come out of a battle unwounded, unscarred—mentally or otherwise—is pretty unrealistic, but it’s surprising how many writers forget how intense and crippling battle can be. Still with the Dresden Files, Knight of the Cross, Michael Carpenter, suffers some horrific injuries that threaten to kick him out of the game, and he’s a character who is a warrior at heart and has seen his fair share of hassle. Nobody can remain seriously unharmed in battle if they battle long enough. Jon Sprunk has this right with the litany of injuries that Caim picks up in his recently completed Shadow Saga. Caim is good, but he still gets hurt, because he’s just a man and men bleed.

Essentially, characters can pick up imperfections as they go along, and while they can just as easily not do, it adds a layer of realism and believability to whatever they’ve been through. To come out of a battle unwounded, unscarred—mentally or otherwise—is pretty unrealistic, but it’s surprising how many writers forget how intense and crippling battle can be. Still with the Dresden Files, Knight of the Cross, Michael Carpenter, suffers some horrific injuries that threaten to kick him out of the game, and he’s a character who is a warrior at heart and has seen his fair share of hassle. Nobody can remain seriously unharmed in battle if they battle long enough. Jon Sprunk has this right with the litany of injuries that Caim picks up in his recently completed Shadow Saga. Caim is good, but he still gets hurt, because he’s just a man and men bleed.

Disabilities—natural, acquired pre- or during the story—and physical imperfections are almost essential to writing good, rounded and believable characters. People get hurt, people are sick, people have diabetes and asthma and long- or short-sightedness. A perfect human is not a perfect character. An old man is going to creak a bit when he moves. A dyslexic spellwright can be powerful. A woman who can barely walk can transform into a bird and fly, fly away.

Title image by DavidRapozaArt.

Well written article Leo. I’ve had the same views for a while now, especially after Rand from (WOT) lost his arm to that fireball.

Indeed, I do like my characters flawed, in terms of personality. That gives them a chance to improve and grow as people. Perfection is hard to relate to. That’s why only the flawed can be flawless.

I am also interested in characters who have to overcome additional hardship due to disability. Reading about such characters makes the us appreciate what we have. A hero always has to overcome both the antagonist as well as their personal battle, to surpass their own limitations as grow. The theme of disability is a prominent one in my writing.

I also just learned this tidbit, which I thought I’d share. Historically, smiths were often portrayed as disabled. This legend may have rose from bronze smiths, who often had to work with lead and arsenic that they had to mix with copper.

Tyrion Lannister springs to mind… Also Glokta from Abercrombie’s First Law trilogy. But yes, these are the exceptions that prove the rule. I wouldn’t want authors to be obliged to insert disabled characters into books for the sake of it, but what is most objectionable is using some kind of disability or difference as a lazy shorthand for “evil”, as in the Evil Albino trope.

As long as you are mentioning ASOIAF characters, why not mention Bran. Who starts out as a very athletic child, and experiences a literal fall from grace

Not to mention Thomas Covenant in Stephen Donaldson’s epic series The Chronicles of Thomas Covenant

Disability inspired my writing. Watching a young person cope with chronic illness showed me strengths of character rarely understood. They didn’t translate as a disability for my mc, at least not a visible one.

Great article. Makes you think.

Thank you so much for this article. As someone with a disability, it is important to see real people in fiction that have various “disabilities” that do not follow stereotypes. It is depressing to see disabled characters included only to see that the author did minimal research on the internet and has no clue how a real person lives their life with that disability. Also, authors need to remember that even if they know one person that has that disability, that that one person does not represent every person with that disability.

Thanks again for this well written and well thoughtout article. I am now off to see if the books and authors listed are in accessible formats or need to be put on my watch list at the end of my LONG reading list.

Hmmm, I think a disability should come naturally to the character, rather than being wrote in to be unique.

The main character of Dragon Outcast (of the Age of Fire series by E.E. Knight) is crippled at the beginning of the book and that gives him some serious troubles throughout the story. (This character is a dragon, by the way, but that doesn’t really ever seem to help him much.) He’s also an outcast without a name. The author simply calls him “the copper” throughout the entire book despite the fact that he is later taken in and named in the story. In dialogue is the only time you hear the copper’s name, and it serves as a constant reminder of the character’s history.

A good article. I really should do a bit more of this, although I am currently writing about an action heroine in her late 60s.

Central to The Chronicles of the Lescari Revolution (by me) there’s Aremil, who in modern terms, has cerebral palsy and in his case is highly dependent on others with no convenient magical answers cropping up…